“The human can be redefined, and the future can be remade too. The question remains: in whose image?”

Michelle N. Huang

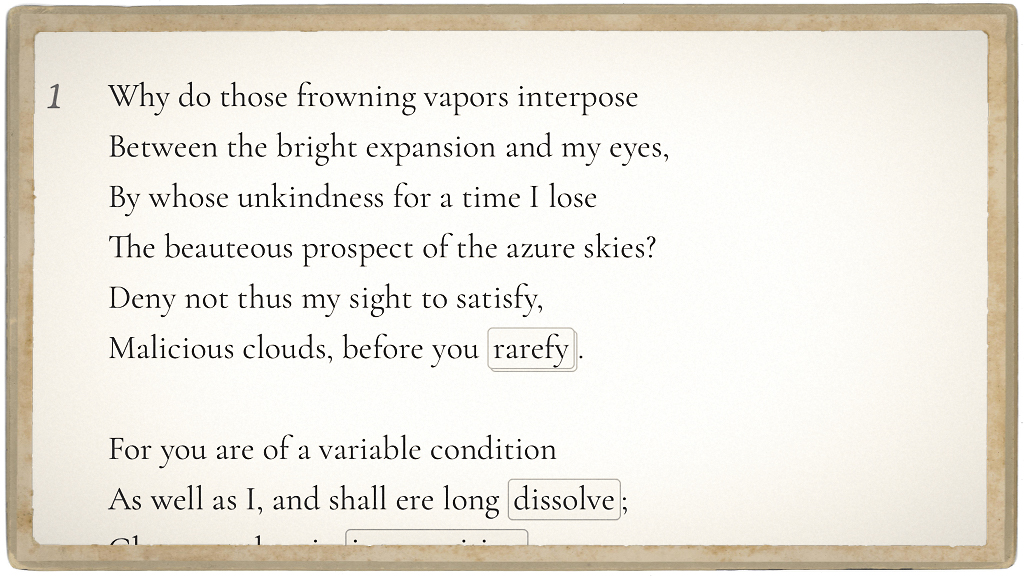

Over the past two years, the Media and Design Studio’s digital storyteller, CA Davis, has been working with English and Asian American Studies assistant professor Michelle N. Huang on the Studio’s latest film essay — INHUMAN FIGURES: Robots, Clones, and Aliens. Based on Huang’s research on Techno-Orientalism and the ways in which racial stereotypes pervade popular American films and television, INHUMAN FIGURES is now streaming as part of the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center’s online exhibits. You can watch it at https://smithsonianapa.org/inhuman-figures/.

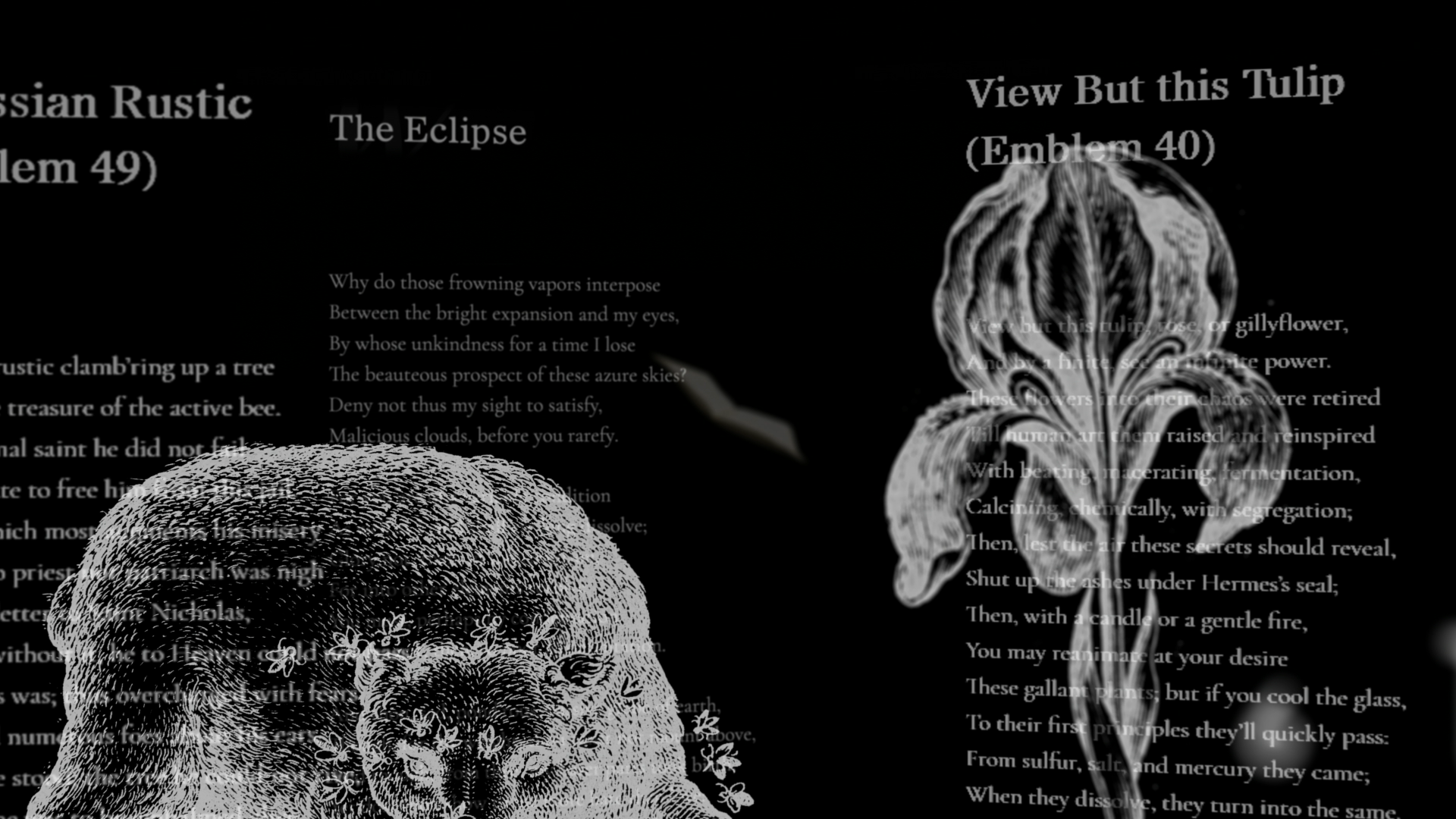

INHUMAN FIGURES examines three popular science fictional archetypes—the robot, clone, and alien—and illuminates the racial logics and histories that underpin them—namely, the tireless worker, the indistinguishable copy, and the forever foreigner. By bringing to light lesser-known and forgotten histories, Huang shows how sci-fi futures are built on the backs of “humans that have [always] been less than human.”

Breaking down examples of popular films such as Ex Machina, Cloud Atlas, and Arrival, the film essay makes visible how these racialized tropes are utilized in the process of U.S. nation-building and future-making. And while popular film and television provides plenty of material to critique, few offer an alternative vision. “There is a limit to how many times you can see naked Asian American clones be thrown in an incinerator without feeling dehumanized yourself,” comments Huang.

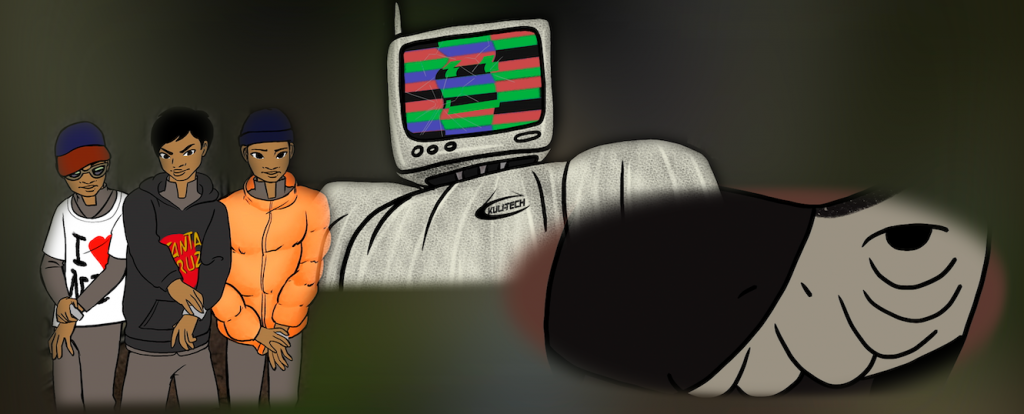

In order to fill the visual gap between the overused stereotypes in dystopian films and the possibilities of reparative speculative futures, the production evolved to incorporate the animation of three independent artists: Chicago local Keith Couture, and Evanston sisters Brittney and Crystal Galloway of the indie animation house, Sleepy Gallows Studio. Much of the production was spent conceptualizing, planning, and iterating the eight minutes of original animations based on a story arc that peels away the facades of these future beings in order to reveal the people living under their masks—no small task for a three-person art team.

And while the film dissected such racial stereotypes about Asian Americans head-on, it is notable that the production team of INHUMAN FIGURES itself reflected the multiracial coalition building that coalesced throughout 2020 amidst a surge in the Movement for Black Lives against police brutality and racial violence. The team’s animators, Brittney and Crystal Galloway, are themselves representative of a burgeoning wave of Afro-Anime enthusiasts whose work is directly inspired by the decades of rich, hand hewn Japanese animation.

“Working on this project has reminded me that there are other ways to animate,” Brittney Galloway reflected. “I was trained in the traditional American way and many of the teachers looked down on anime. The mixing of frame rates is much more common in Japanese animation as they are still experimenting as opposed to the West where it’s ‘perfected.’ While there are shots I wish I had more time on, overall, I don’t think the production suffered. In my future endeavors, this project will be a reminder that there’s always a way to make things more practical without sacrificing too much quality.”

INHUMAN FIGURES is a 24-minute film accessible free of charge via the Smithsonian’s Asian Pacific American Center online exhibit. Visit the exhibit here:https://smithsonianapa.org/inhuman-figures/