On Building a 21st Century Reading Experience with a 17th Century Poet

In 1974, when The Riverside Shakespeare was published by Houghton Mifflin, the venerated two-volume collection of Shakespeare’s poems and plays was thick as a Tewkesbury mustard. The edition came loaded with extras. So many extras—in the form of notes, footnotes, critical essays, justifications for modernized language, photographic inserts and more—that Stephen Booth, reviewing the 2,057-page collection for the New York Review of Books, feared its monumental size “would cause iatrogenic malnutrition in students” and would be too heavy to carry to class.

Today, four decades and two editions later, many students of Shakespeare are still hefting that “big, ugly” Riverside like seven pounds of early modern flesh. Despite the bracing sticker price of $200, a great many professors, sold on the critical bona fides of those extras and lured by the convenience of everyone being on the same translucent page, require students to buy it.

Booth believed that Houghton Mifflin’s sales strategy—bundling critical notes pitched to faculty in order to tap the student market—positioned the student as a permanent outsider. The Riverside failed as an aesthetic experience, he wrote, because “its concerns are usually different from, inconsistent with, and invidious to the concerns of those who will read it.” It’s hard to make something good. Harder still when a crucial piece of that something is authored by someone else, for someone else.

Happily, there are technological affordances that enable us to meet literary figures on more intimate terms, free of editorial cruft. We can, for instance, build an edition around a poet whose life briefly overlapped with Shakespeare’s. And we can front that edition with contributions by critics and scholars—as did the Riverside. Crucially, though, we can make those notes and essays disappear with a tap, leaving nothing visible to the reader but the original ink-smudged manuscript. And we can make it free.

With The Pulter Project: Poet in the Making, edited by Wendy Wall and Leah Knight, developed by Northwestern’s Media and Design Studio, that’s what we did.

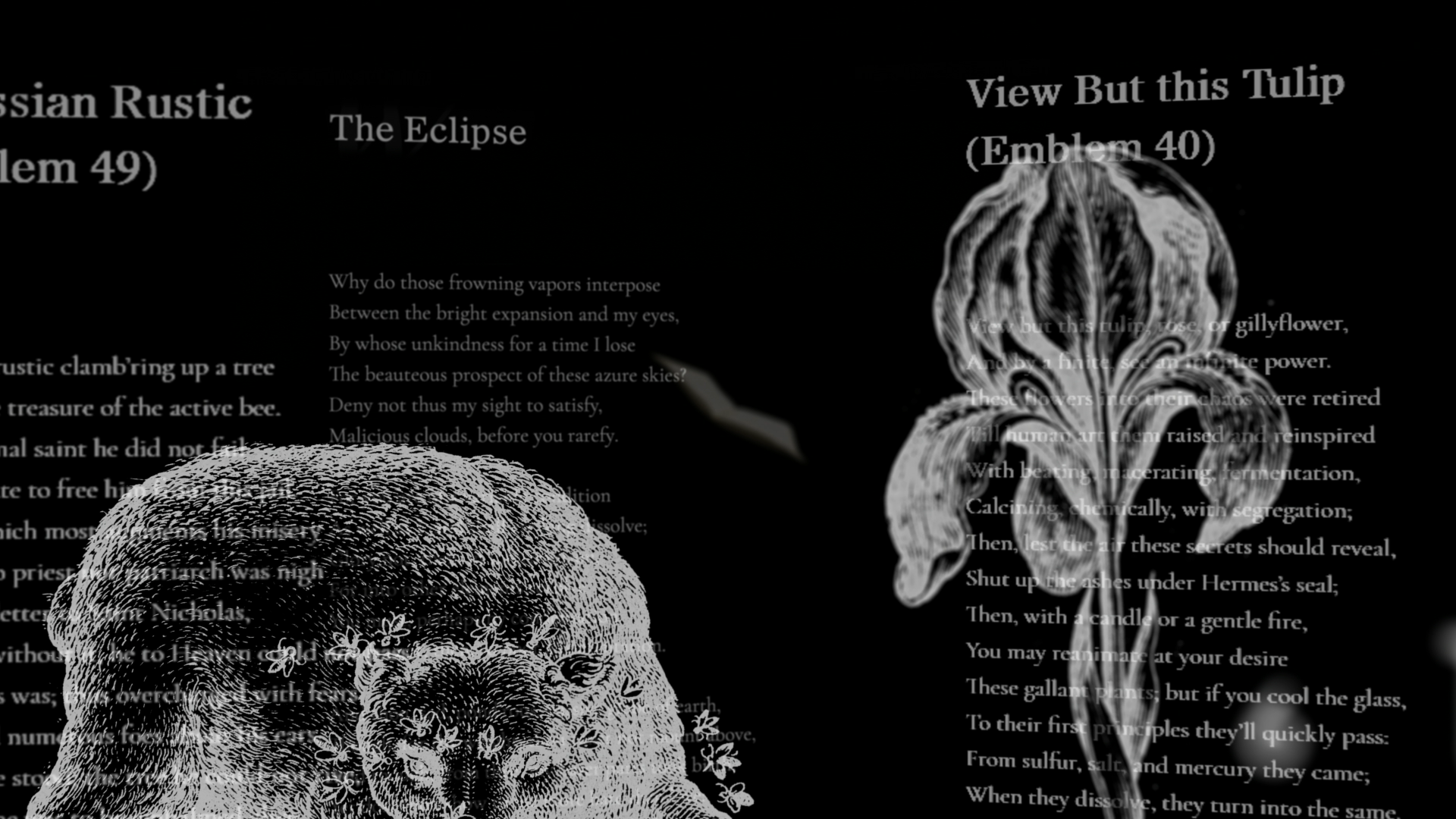

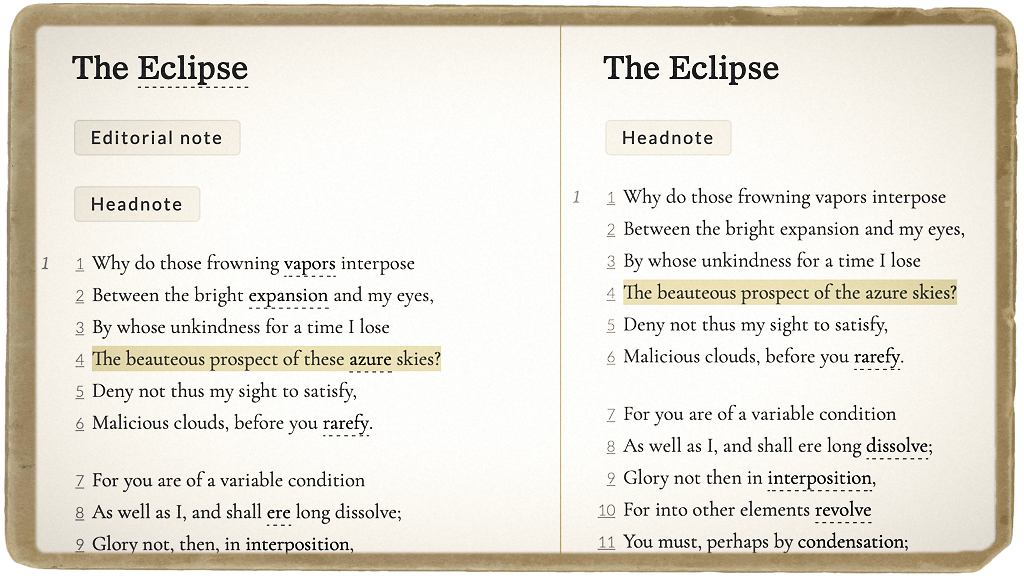

The Pulter Project is a digital collection of Hester Pulter’s poetry, engineered to adapt to the concerns of all who will read it. Readers seeking minimal interruption and basic editorial notes can activate a pared-down elemental edition, while those seeking additional context and commentary can enable the site’s editorially beefed-up amplified edition. The cumulative effect might be compared to visiting a museum that not only displays works on the wall, but gives us a chance to enter into that work, the making of it, the reception of it. The Pulter Project is also outfitted with a tool that compares editions side-by-side for a granular study in how poems evolve as they’re touched by different editors—as well as numerous other means of accessing the verse of this 17th century artist whose work was nearly lost to history.

Nobody seems to know a whole lot about the route taken by Pulter’s calfskin-bound manuscript before it was found by Mark Robson, a graduate student with a keen eye for verse, in a Leeds University archive in 1996. Prior to Robson’s recovery, the manuscript was owned by Gilbert Ingefield, a former architect and book collector who also happened to be the mayor of London. Ingefield auctioned off the book at Christie’s in 1975, when it was acquired by Leeds.

The Pulter Project interface was designed by Sergei Kalugin, a Russia-born developer who maintains exacting diets and competes in triathlons. “The initial design,” he says, “was based on the fact that the only real thing that we have here is Pulter’s manuscript. It’s the pillar. I was convinced from the very beginning that the reading itself should be the sole focus of the interface.” He notes that even printouts of the poems, the overlooked stepchild of screen-centric digital publishing, are intended to please the eye.

“Early on,” says Kalugin, “as we researched other digital editions, one thing struck me: the default mode for pretty much all of them was severe overload. I didn’t like that. I tried to avoid that overwhelming quality. With the Pulter Project, we wanted the user to feel comfortable doing one thing. Reading.”

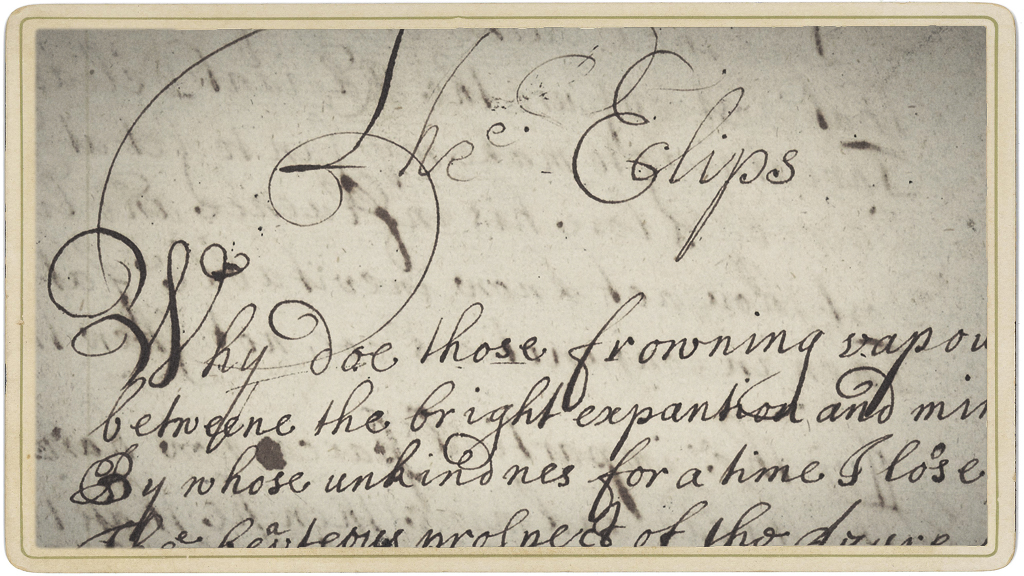

Among the site’s more poignant features is access to scans of Pulter’s manuscript. There’s an inescapable intimacy to these hand-lettered pages. That this should be meaningful probably says more about our touchscreen era than anything else, when the mortal sweat of a made thing is routinely concealed from us. It seems not to matter that most of these poems were copied from earlier drafts by a scribe rather than Pulter herself (though corrections believed to be in Pulter’s hand are laced throughout the manuscript).

What does matter is that a reader today can glimpse how literature was made in the 17th century, before print culture dominated. Hint: it’s maybe not that different than the 21st century, when nearly all writers continue to rely on coteries of trusted readers, friends, and frenemies. This is one of many ways The Pulter Project argues, through its breadth of features—the ability to compare editions, the ability to offer multiple edits of Pulter’s poems in a way that’s transparent to the reader—that literature is rarely, if ever, the work of one.

Detail of “The Eclipse,” from Pulter’s manuscript, circa 1660.

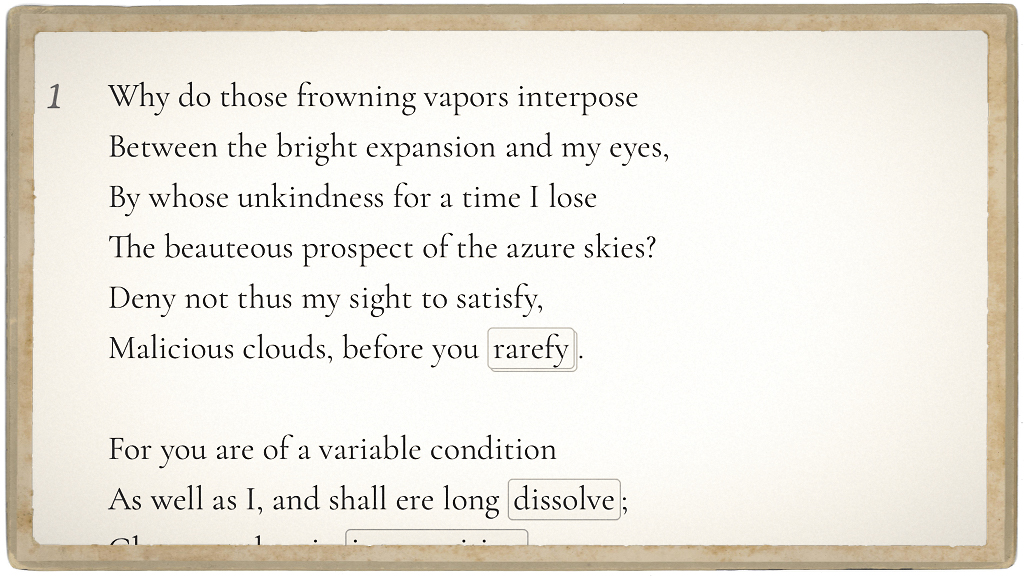

Readers can view the elemental edition of “The Eclipse” for a minimalist rendering of the poem without visible editorial intervention.

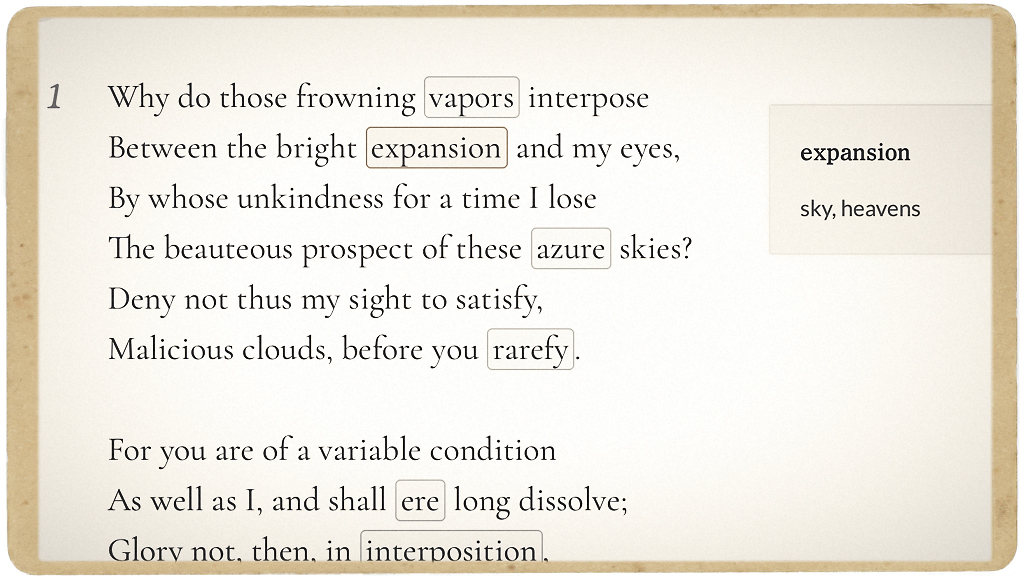

Editorial notes reside in the background until activated by the reader.

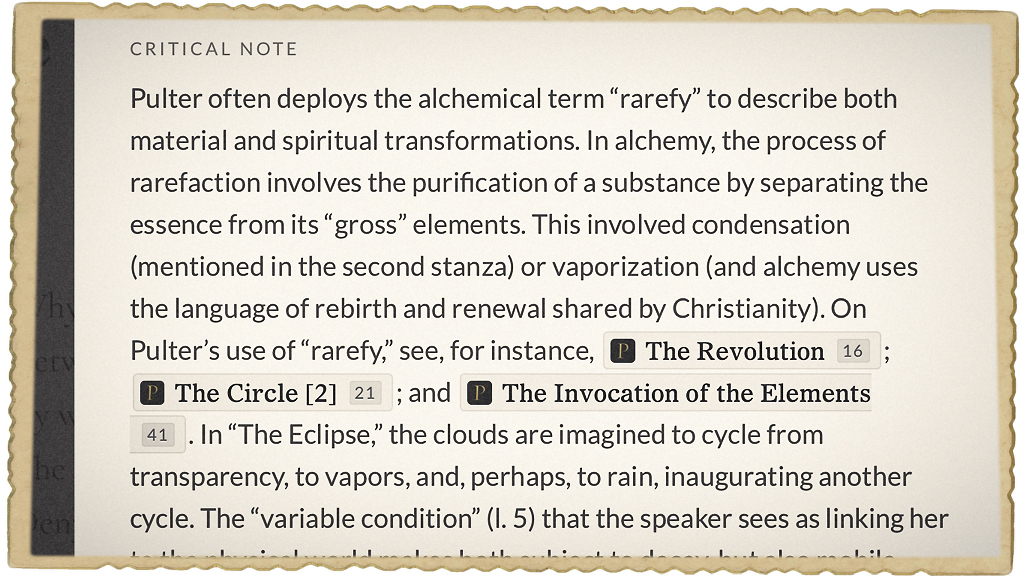

The amplified edition of “The Eclipse” differs from the elemental text, and also indicates critical notes…

…contributed by literary scholars, critics and editors.

Different editions can also be compared side-by-side.