It’s holiday time. Time for big dinners, friends, family, and cheer. At the dinner table there might be those half-interested questions of “What do you do?” or “How is your work going?” This month, after attending the 10th annual Chicago Colloquium on Digital Humanities and Computer Science (DHCS), followed by an exciting talk by Mark Guzdial on how to boost society’s computer literacy, my response will be energetic and as clear as Ralph Parker asking Santa for a Red Ryder BB rifle : “Work has never been better! Increased access to tools and digital literacy are critical to scholarship and instruction of the humanities, and I’m happy to be a part of it!”

But it’s never that easy.

When I tell people what I do, after they fully digest it with coffee, one of the questions I am asked by skeptics in the family, is why the humanities — be it history, art, and/or language and literature studies — need involve computing or computer science. Perhaps they’re imagining classic tools: books, paint brushes, and in-person lectures and discussions, as they grimace at the term “digital humanities,” and wonder if newer technology isn’t just a distraction from deep investigation of the core disciplines, saying things like “Whatever happened to just reading?” Ironically, It turns out that even some of the biggest said-to-be digital humanities scholars also eschew the notion of digital humanities, not because they think technology shouldn’t have a place, but that instead that it should be so integral to humanistic study that there shouldn’t be any segregational distinction made for using digital tools. So, gee whiz, is there really a digital humanities?

Yes, Virginia, there is a Digital Humanities. Or at least the National Endowment for the Humanities thinks so…for now.

The view from DHCS 2015

Regenstein Library at University of Chicago, site of the DHCS 2015 Conference. (Photo: Mark Schaefer)

If there is such thing as the Digital Humanities, it seems fair to sum up a bit about what’s happening in the field and how it might relate to the rest of the “analog?” humanities. Your MMLC team: Cecile, Mark, Sergei, and I were at the DHCS conference held last month at the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library (a Walter Netsch-designed brutalist architecture sibling of Northwestern’s Library) which sits in an odd juxtaposition to the extraordinarily beautiful and high-tech Mansueto Library — an elegant venue for the ordinary reading my aunt champions at the dinner table.

I was even more delighted that Sergei and I were able to participate in a panel where we, together with Michal Ginsburg from the Department of French and Italian, shared the latest versions of the graphs of characters and communities in Hugo’s Les Miserables, along with an important summation of our processes and methodologies.

Northwestern had great representation overall, ranging from members of NUIT, to members of the Northwestern Library (talking about the #Undeadtech project), to some key MMLC faculty collaborators like Sylvester Johnson and Michael Kramer.

Bridging dimensions, Harlan Wallach and I expertly wielded our iPhones to cover much of the weekend’s events via Twitter (check out the DHCS-2015 Storify). Once again, Twitter remains the preferred subspace communication channel within the #DigitalHumanities community.

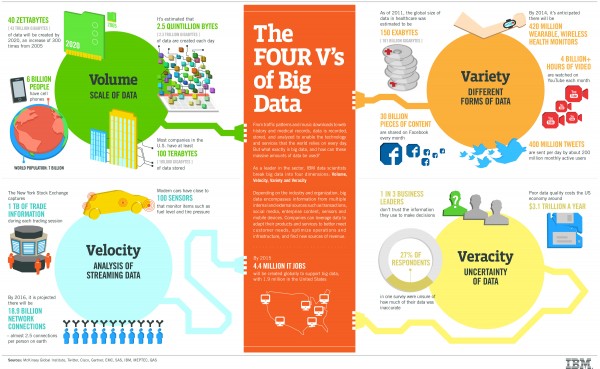

Big Data: Science brings three ‘V’s, the Humanities bring a fourth: “Veracity”

The event opened with a welcome from the U of C Assistant Vice President for Research Computing and Director of the Research Computing Center, H. Birali Runesha. According to Runesha, most of the applications of big data to problems in the sciences have been about the three Vs, first characterized in 2001 as: Volume, Velocity, and Variety. However, together with the advent of the Digital Humanities, he believes there is an equally important fourth V that is emerging: Veracity. How certain are we about the data? The humanities are effectively bringing a much needed background of critical analysis into the world of big data, and the result is a much richer approach.

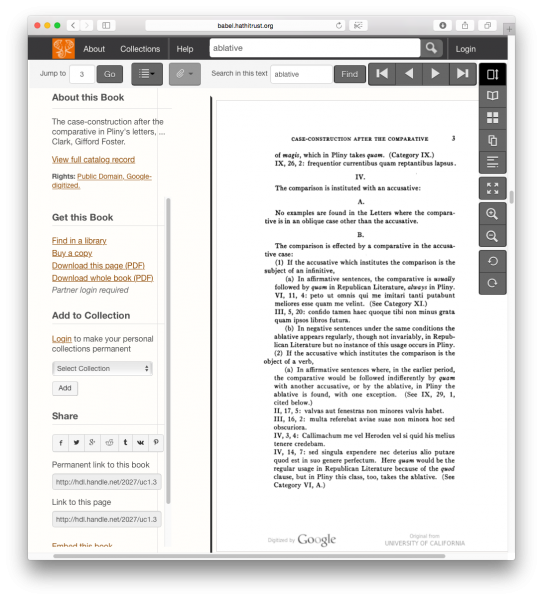

Asking deeper questions about the veracity of data is important and it is one of the biggest questions confronting one of the largest-scale and well-known digital humanities projects: the Hathi Trust, a partnership of academic & research institutions working to digitize a collection of millions of titles from libraries around the world. In an update session led by Sayan Bhattacharyya, we learned that with the help of several libraries and technology from Google, Hathi has now digitized nearly 5 million public domain volumes — which might seem big, but the textual “big data” of these books is a mere 1.4 terabytes: roughly 2-10 times the hard drive size of a modern computer. Bhattacharyya points out that this is not very big by science standards. And, quickly thinking about my participation in another nerdy data project, SETI, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, I know this to be absolutely true. For example, the upcoming Square Kilometer Array (SKA) will easily collect thousands of terabytes of data each day from outer space in a search for intelligent life.

But this doesn’t mean that the humanistic data found in the Hathi Trust databases isn’t still big in its own right. It is after all, very dense and deliberate data that originates from a core of the humanities. Bhattacharayya further explains the Hathi trust data is certainly big data because most humanists work on very small data: a few texts at a time. Thus, the ability to algorithmically explore the text of millions of volumes at once allows an amazing opportunity for humanistic insight — but only if that data is correct.

Why wouldn’t it be correct? To build such a large database, the Hathi Trust has been scanning books from several libraries with automated tools for nearly seven years. After imaging, the page of each book is “read” and interpreted by a computer using a Optical Character Recognition (OCR). Unfortunately, this entire process leads to some occasional, significant errors. The resulting error-laden or “dirty” text may give a computer program a sense of what it’s about, but because humanists are often interested in very specific nuances, clean, accurate texts are imperative.

Perhaps Martin Mueller said it best when he said “Readers want clean texts like grandparents want clean children at the dinner table,” to the members of Hathi Trust, stressing that it is important for the textual data to be accurate, not just abundant and quickly searchable.

The challenge of the veracity of data becomes even more pronounced when the very data itself is hidden. In addition to the very liberal access to public domain works, the Hathi Trust plans to offer algorithmic access to millions of copyright works as well: meaning that scholars can write programs to analyze the protected texts. What follows, then, is an immense issue of trust: if scholars can’t access the texts to verify their accuracy, how then can they trust the results of programs that use those hidden texts? This issue is still being worked out.

Even at a conference focused on digital opportunities, there are members in the audience who, like my aunt, inquire about the impact of these digital avenues on ordinary reading. In response, Bhattacharayya cited a sobering statistic that as few as 25% of students actually bother to read assigned reading assignments completely (which I did find corroborated by this study). So, it seems there can only be a benefit to these newer ways of working with texts.

Metacanon: What really is a must-read?

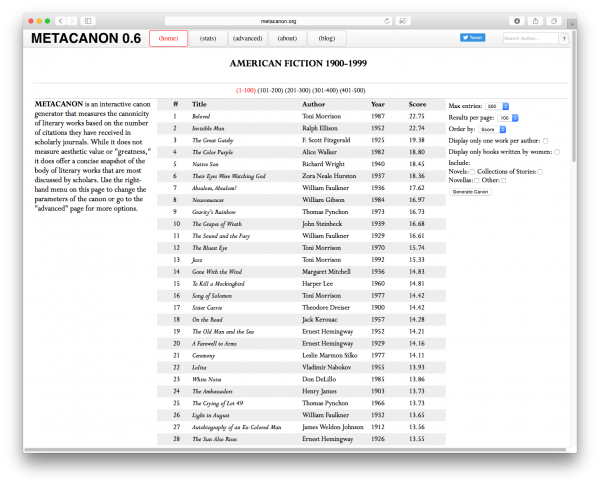

But are we reading the right things? This question has been so elegantly exploded thanks to Metacanon.org. A project of Nathaniel Conroy’s, a Ph.D. English student at Brown University, Metacanon takes the very staple of formative literature courses — a canonical list of readings — and imagines a totally different and flexible way to derive the literature of greatest significance. In other words, despite what any one authority says is canonical author or work, what really are the canonical works?

According to Metacanon’s calculation, Tony Morrison’s Beloved is the most important reading of 20th century American fiction.

So, rather than present a New York Times best seller list or a collection of titles ranked by an academic committee, Metacanon computes the relative significance of american fictional works according to a configurable formula which includes: numbers of times the title is mentioned in scholarly works found in Google Scholar and JSTOR as well as the American Literary History, and American Literature journals. Fictional titles also receive extra score points, by default, if they received a Pulitzer Prize or National Book Award. Yet the genius of Metacanon is that the base formula is configurable to a variety of criteria.

At a minimum, the tool is highly insightful, offering a fresh alternative to lists that are too often overwhelmingly composed of white, male authors. The methodology by which it identifies book citations is configurable but not in every way. For example, the algorithm faces challenges when assessing the rank of book titles which have a single word title, like “Beloved.” How does the program know if the mention is about the book title or about the adjective? Foreseeing the problem, Conroy applied a bias to correct for the number of false positive citations that would occur based on the natural frequency of the word. For example, while the word “beloved” frequently occurs in English, an approximation of the naturally occurring frequency of the word “beloved” is subtracted from the results so that, in theory, only the number of times Beloved refers to a proper title should remain.

Digital Humanities: Literature and Language

I was happy to see that literature and language had prominent positions at the DHCS colloquia. Three of the first-day poster sessions dealt with methods and tools in various stages of development that will complement language instruction and study:

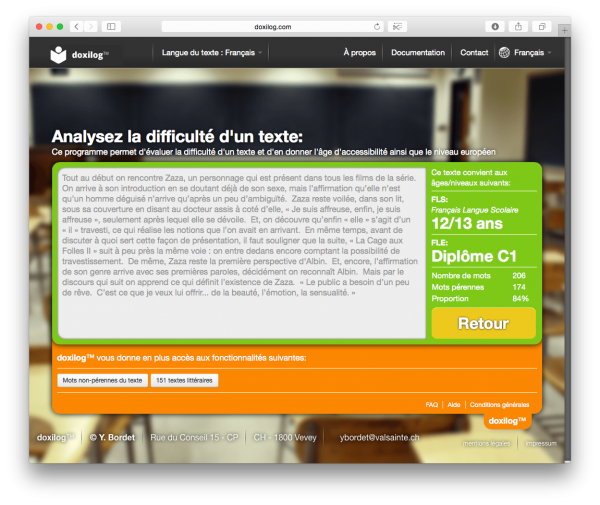

- The Doxilog Project, an Educational Computer App — Yvon Bordet (Université de Franche-Comté)

- Digitizing the Jingdian shiwen (經典釋文): Deriving a Lexical Database from Ancient Glosses — Jeffrey Tharsen and Hantao Wang (University of Chicago)

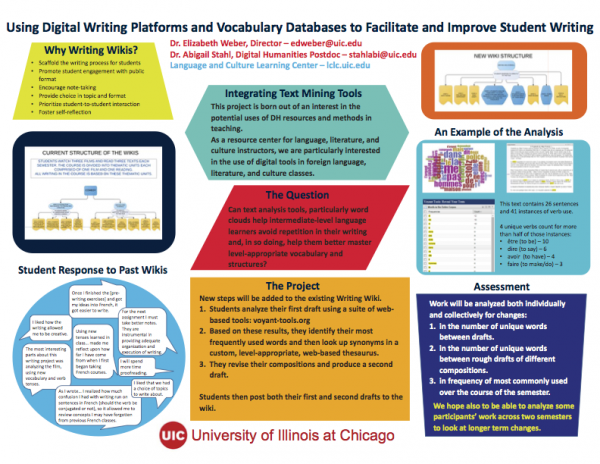

- Using Digital Writing Platforms and Vocabulary Databases to Facilitate and Improve Student Writing — Elizabeth Dolly Weber and Abigail Stahl (University of Illinois at Chicago)

Doxilog analyzes some text I wrote long ago as roughly C1 level text: roughly understandable by a 12-13 year old native speaker. I might beg to differ.

The Doxilog project attempts to provide two utilities to language instructors: (1) assessment of a text’s vocabulary difficulty, according to CEFR levels, (2) access to classical texts, both as an e-book and an audio book that match a particular CEFR level. The computation of a level is based on a ratio of roughly 1500 “perennial” (common) to “non-perennial” (less-common) words in a given text. It is a very basic algorithm that requires larger texts to produce the best results. And while some may not agree with the particular methodology of how difficulty levels are assigned, the electronic text repository will be a boon to those searching for level-appropriate classical texts.

Graduate students Jeffrey Tharsen and Hantao Wang from the University of Chicago have embarked on an project to create a Unicode edition of the Jungian shiwen (經典釋文), a 30-volume work from the year 589 written by scholar Lu Deming (陸德明). Conceived as a dictionary and glossary to classical Chinese literature written thus-far, it contains valuable fanqie (反切) annotations for pronunciations of characters in classic Chinese texts so modern speakers have some idea of how the ancient characters were pronounced.

E.D. Weber and A. Stahl (UIC) present an experimental model for improving student writing through the use of DH text analysis tools.

From UIC, Elizabeth Dolly Weber and Abigail Stahl presented a conceptual platform for students to become better writers through the use of digital humanities tools. They plan to start with a common writing platform, the wiki, and add additional DH text analysis tools like Voyant to the students’ authoring and proofing workflow. Voyant will quickly identify areas of repetition in the students’ work, and will encourage them to use a greater variety of vocabulary. Through use of the wiki platform, they will be able to quickly ascertain the outcomes of using text analysis tools during the students authoring process.

Digital Humanities: Many things, many algorithms

As is true of many digital humanities conferences, a number of the presentations dealt with the subject of DH itself. Gregory Crane and Tara McPherson, two A-list names in the DH community, offered keynote presentations that touched upon new understandings for the genesis and future of digital humanities. From Crane, who has faculty appointments both in the USA and in Germany, we learned how the academic systems of our two countries differ. For example, in Germany, even without the advent of digital applications, the Humanities are Wissenschaft and occupy a priority space on par with the sciences. This gives them access to a great number of government funding opportunities.

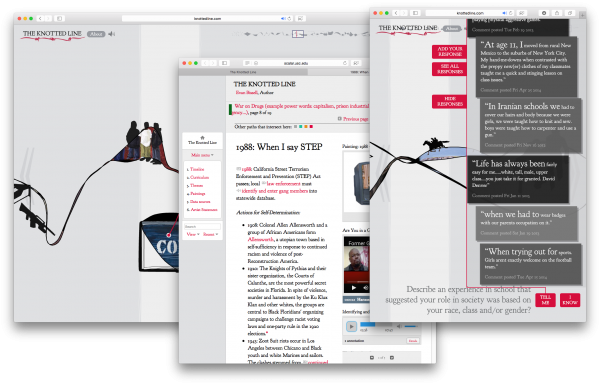

The Knotted Line is one of the most cited example uses of the Scalar – a platform for creating multi-modal narratives.

Tara McPherson began her much anticipated keynote at the culmination of the first day’s activities. McPherson, who teaches at the University of Southern California has made several major contributions to the logos and telos of the digital humanities field. Her work on the “Vectors” multimedia journal (similar to Northwestern’s TriQuarterly Online) led to the development of “Scalar,” a widely-used multi-modal publishing platform by the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture, where McPherson is the principal investigator. In her keynote, she called to attention a number of ways that digital humanities can frame inquiry into art, design, feminism, and the very formats of scholarship itself. For example, she wondered “Can software tools and platforms be feminist?” Citing the scholarship undertaken with Scalar, she wondered how digital humanities can offer an opportunity for scholarship that goes beyond text, further engages the senses, and allows for multiple modes of expression.

As the digital humanities field still works to define and unify itself, the best of Tara McPherson’s presentation recalled some of the work of early information designers, such as Charles and Ray Eames of the Eames Office for IBM. If the important claim was that Eames’s role is just as important to the digital humanities today as the role of Father Roberto Busa, I will definitely agree. While it’s true that Busa’s Index Thomisticus ignited the field of humanities computing between 1949 and 1979, the Eames’ groundbreaking 1977 “Powers of Ten” fluidly demonstrated scale using an appropriate medium, and went on to inspire critical ways of seeing things at various zoom levels: texts, art, stories, or just about anything.

By the end of both keynote presentations, I was left in awe of the transcendent elegance the digital humanities might offer while attempting to answer the larger questions with reimagined scholarship. Yet, from the content of every presentation, I am grounded in a hard reality that DH is also about tools, lots of tools: programs, editing and publishing platforms, acquisition and presentation devices. And, it seems, more than any lofty purpose or goal, what best unifies the digital humanities field seems to be the design and application of algorithmic approaches. Algorithms are something that have traditionally remained in a primarily science and engineering domain — but is that where they should uniquely remain? More and more, we see that there is room for programming and a better understanding of process throughout the liberal arts.

A call for computer science in the liberal arts

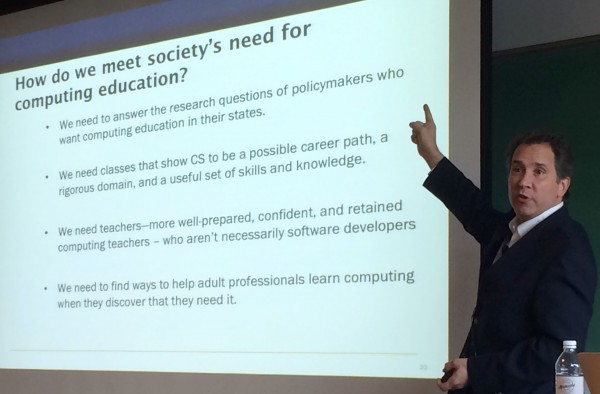

It seemed all too providential that one of the nation’s largest boosters of Computer Science education for everyone, Mark Guzdial, should be invited to Northwestern within a few weeks of the DHCS conference at a McCormick CS+X event. His presentation focused on the requirements for a computing literate society.

As Guzdial pointed out, the question about whether computer science belongs in humanities education is definitely not a new one. In some sense it borrows from an earlier observation, from 1959, when Charles Percy Snow noticed a growing gap between scientists and humanists.

His lecture and eventual book, “The Two Cultures” underscored how the chasm between the groups hindered forward progress. Then, as now, there were differences of societal engagement: humanists were often involved with the public, while scientists were often isolated and not well understood by the dominant culture. To Snow’s own example: it was expected that the dominant culture know the works of Shakespeare, but not always equally expected of society to know the second law of Thermodynamics. Snow was an optimist, however, and imagined the possibility of a third culture made up of those capable of bridging the gap between scientists and humanists.

To further explain the need for the understanding of computer science and algorithms, Guzdial cited the fear of algorithms that had been felt by some in 2007, the year prior to the economic collapse. To many, it seemed that more and more of the world was in control of programs that very few knew anything about. Amazingly, these fears echoed the very prophetic words of C.P. Snow who was fearful of a future where “a handful of people, having no relation to the will of society, having no communication with the rest of society, will be taking decisions in secret which are going to affect our lives in the deepest sense.”

As an aside, while scientists have undoubtedly become more public (think Neil deGrasse Tyson, or Bill Nye) I sometimes wonder if the “Third Culture” isn’t still a largely unpopulated land of opportunity. What if computer science can offer the next greatest chance of breaking down a traditional barrier between humanities and science? What if the digital humanities can thrive in this third space?

Taking a look at AP test statistics, Guzdial noted that AP Calculus has seen an impressive growth among future college students – not just engineers and scientists. This is because the students know the course will be valuable to a multitude of degree options. By contrast, although there is a computer science AP test, its numbers have remained flat: students see it as something that is pertinent only to a computer science or technical major.

From this simple contrast, it is clear that computer science — despite its importance — faces a number of challenges to achieving greater significance in the liberal arts curriculum, both in higher education and in the schooling leading to higher education.

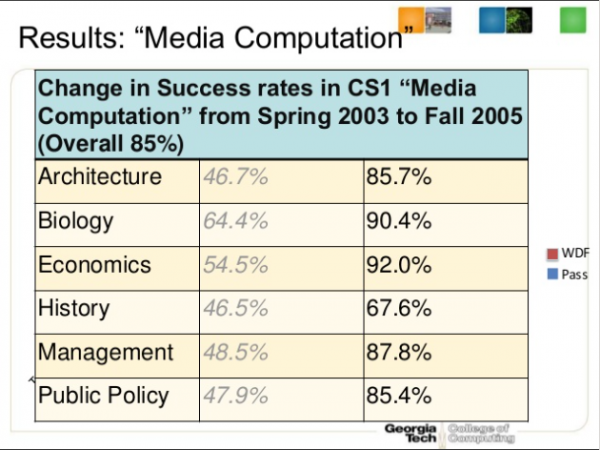

Slide from Requirements for a Computing Literate Society which demonstrates the improvement in success rates after an introductory computer science class is made more relevant to non-majors.

To offer a model of improved uptake of computer science concepts, Guzdial shared the story of Computer Science 101 at his home institution, Georgia Tech. Completing a computer science course there has been mandatory since 1999. Through 2003, however, the approach to teaching computer science was largely modeled on the theoretical bases that majors would need. Students found the theoretical approach “tedious, boring, and irrelevant.” So, the introductory computer science course was revised to be relevant, focusing on concrete examples of what computers are good for.

Guzdial also recognizes that some of the change in higher education must come from the computer science departments themselves having said that sometimes, “they, more than STEM disciplines, think that CS is innate, either that you have it or you don’t.”

At the secondary educational level in his home state of Georgia, Guzdial strives to provide CS teachers with the resources that they need: a sense of identity; confidence in their ability to teach; and more professional learning, both content knowledge (CK) and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). If he is successful, other state curricula may follow suit.

Guzdial’s Media Computation course at Georgia Tech provides an inspiration for the direction we might take on our own campus, finding ways to integrate computer science into the curricula in meaningful and relevant ways.

Perhaps we can do the same by preparing the next generation of “third culture” scholars who are able to bridge humanities and computer science through the improved study of the digital humanities.

Meanwhile, I’ve got a good book to read.